‘Under One Sky’ Deconstructed

“Kabilin (Tausug)”

acrylic on canvas, 2014

Beyond the Building Blocks of Art

I have made a commitment to an artistic practice that highlights projects beyond aesthetics since early in my undergraduate training in painting. There are much important matters at stake than just looking at unique forms; techniques in the material manipulation; the meaningful (personal) themes unfolding in various mediums (two-, three-dimensional, time-based, installation and performative works); and the curatorial narrative in a particular given space. Though all creations emanate from these, they eventually become stale. Artists have to create visual (and auditory and even moving) metaphors that make connections.

Looking back, this art projectmade me realizeagain that the visual arts(or any form of art for that matter) hasa greater social role thatis important for thePhilippines—and therest of the EAGA region. This reflection brought me back to my early artistic engagement, when I was still a young painter sent as one of the Filipino representatives in Brunei Darussalam with four other young artists (among them, Emmanuel Garibay and CarloTadiar) during the 6th ASEAN Visual Art Workshop and Exhibition organized by the ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information (ASEAN-COCI) in 1988. There, I found more value in art when it is connected with the more important notions of people and place than just geography per se. Though we begin our association with the latter, this connection is more magnified when looking and doing art with your neighbours, who also find meanings in the same vein.

I would want to have more artistic encounters in more spaces in the coming years to encourage more artistic interactions, which are intercultural engagements with our Southeast Asian neighbours. This revitalized state-sponsored event also created more meaningful artistic engagements in the region in addition to the ongoing initiatives coming from the artists’ communities. This is reinforcing what has been done through art linkages early on coming from our capital cities. These re-connections conjure rich realizations in our lives beyond the shaking of the hands and signing of trade agreements.

Each encounter begins a meeting of strangers and eventually forms acquaintances, creating a sense of belonging. It is like looking at the mirror and seeing a familiar face looking back. If we can replicate such engagements in other peripheral spaces, it reinforces the cultural connections what we have been missing in the peripheries of our nations, unlike the contemporary visual arts experiences between the capital cities. Encourage regions from the margins to participate. There are more rewards in strengthening the nation and diversifying our identities in the EAGA.

I’m sure this is not the case for coastal communities in the EAGA region, which has not ceased its connections for centuries, to be relational in terms of language, family histories, culture and trade, livelihood and faith, and shared sensibility. These relationships also include historical frictions that have not healed today as our national and contentious borders had been established from colonial control towards our respective republics.

As a matter of fact, this focus on the arts and culture in this sub-region during the Philippine-hosted golden anniversary of the ASEAN in 2017 is a belated exercise among our top leadership. Isn’t it that we should strengthen first our post-nation partnerships by rekindling what binds our cultural spirits before we do trade? Why use art as a means to re-connect back our regions coming from the heart of Borneo and the Sulu-Sulawesi marine eco-region? The value of the arts is beyond the quantifying it in EAGA’s currencies (that is, the dollar, rupiah, ringgit and peso), it is something intergenerational and ingrained in each of our artistic forms and cultures.

I quote George Simmel (“The Field of Sociology,” 1950) from Vanessa May’s section on the personal and the social (“Why a Sociology of Personal Life,” 2011): “(I)f we think of society as a painting, the closer we get to it, the more clearly we can distinguish the individual people in the picture. But as we move further away, we can no longer see the details so clearly, and can instead appreciate the overall structure of the painting. We may interpret this as observing two separate entities (individual people and society), but both are in fact, views of the same thing seen differently, depending on our distance from it.”

“Under One Sky” is one of our symbols of our re-connection in the EAGA through the Budayaw: The BIMP-EAGA Festival of Cultures, hopefully one of the many that we continue to create along the way. We can be who we are when we are our creative selves.

According to Vanessa May on the section on the meaning of place (“Personal Life in Public Spaces,” 2011), “a place that we have a sense of belonging to is also likely to have significance for our sense of self. We create a sense of belonging to places which we feel reflect who we are and thus create a sense of self ‘though place.’” She further quotes Tilley (“A Phenomenology of Landscape,” 1994) “that our collective and personal identities are partly based on place because we understand ourselves as people from a particular place.”

“Under One Sky” became a worthwhile collective undertaking when the visual artists were coming from intergenerational practitioners, and the unique representations conjured up from their locale and studio spaces. Traditionally, contemporary visual arts practices are solo by nature. By directing them and showing the works of art together, it would make them think: “Where am I in my current art practice compared to what my artistic neighbours are doing?” This initial inquiry will engender many possible answers from each participating artist as he or she investigates the creative works of the participating artists from Malaysia (from the states of Sabah and Sarawak and the Federal Territory of Labuan) and the entire sultanate of Brunei Darussalam. We dearly missed the participation of Indonesian visual artists coming from the provinces of Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku and West Papua. Hopefully, in the next iteration (Budayaw 2019 in Kuching), we should have better communication and openness, and let the visual artists coming from those Indonesian provinces know they are part of the EAGA community. We expected challenges and adjustments as communication and diplomatic protocols reach out to each other. This is technically a pioneering effort within the EAGA since agreeing to set up its fifth development pillar, the Socio- cultural and Education pillar.

Celebrating our Humanity Together

“Under One Sky” is a first high-profile engagement for this sub-region of Southeast Asia. Although the Sulu and Sulawesi coastal communities have been connected for a long time, a lot has changed since. The nightmarish realities of colonial rule reconfigured not only borders and beliefs, but also the fate of nations that linger up to the twenty-first century.

The visual arts exhibition component of 2017 Budayaw: The BIMP-EAGA Festival of Cultures attempted to re-connect the island region what was once affairs of nation-states, like the seas that reach across these places within the EAGA, the concept articulated fully by Al-Nezzar Ali, the artistic director of Budayaw 2017:1

“Under One Sky,” a festival component, aims to celebrate the notion that there is a common ground, that as part of the Brunei Darussalam-Indonesia-Malaysia-Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA), we can all walk in search of peace and respect in this world. It is also a concept that all of humanity lives under one sky and that, therefore, any community cannot operate as a solitary creature.

Thus, the compositions exhibited in both the installation art piece and the underlying exhibitions explore and interweave the many different styles, genres and traditions at work in today’s dynamic visual arts scene within the BIMP-EAGA.

Moreover, Budayaw 2017 aimed at this pioneering event to strengthen the artistic and cultural engagements in this sub- region beyond interactions among national governments, the geopolitical and socio dynamics, investment portfolio matching, and the economics of tourism to go deeper into kinship of traditions, cultural reconnections and contemporary artistic convergences. Budayaw is a fusion of budaya and dayaw.

Both mean the celebration and gathering together of cultures.

“Under One Sky” selected artists that engage in shared visioning in a philosophical and practical way, emphasizing originality that strongly defines individual roots and creates conditions for enabling emerging capacities and shifting worldviews.

The desired outputs from these creative endeavours project a common vision of a community of cohesive, equitable and harmonious societies, bound together in solidarity for deeper understanding and cooperation through expressions that shape local identities—as individuals, as a nation, and as a region. In lieu, it is important to anchor culture and the arts as enduring factors to further deepen appreciation for the sub-region’s diverse cultures and traditions, and strengthen the sense of belonging and regional identity in the making of a people- centred, people-oriented BIMP-EAGA with an increasing role in the global community.

Instead of assigning spaces to the participating nations and the selected works from the Philippines and having another separate exhibition area for works coming from provinces in Mindanao and Palawan, “Under One Sky” showcased works from the geographical peripheries of the Philippine archipelago (that is the Mindanao island region and Palawan province) and the EAGA region in an engaging visual dialogue by utilizing the atrium space of Veranza Mall in General Santos City for that purpose.

Though we wanted it to be a thematic undertaking, it would not be possible to request new commissions from the visual artists’ communities in a short period of time. The selection process was based on recent created pieces for consideration to the respective country curators of Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

The curatorial component of the Philippines had to thread together the visual narratives based on the themes of the individual works than on any other criteria. These most likely were the shared life experiences in the EAGA. This decision hoped to strengthen engagements between the works of art by finding which piece would resonate better when both or more works are having a visual dialogue together as the viewing public move about the exhibition space. The discourse generated would not just be between works in proximity with each other. It could be from one thematic cluster to another, or an art piece that would linger in the mind of the viewer as he or she moves to the other works. These ephemeral and intangible impressions forming in the minds and hearts of the viewers would encourage them to engage with the artists present at the exhibition.

“Under One Sky” re-established my connections with the ASEAN artistic community that began almost three decades ago (prior to the establishment of the BIMP- EAGA) by finding ways to reconnect with Osman Mohammad as the artist-curator for Brunei Darussalam. He was one of my mentors when five student artists represented the Philippines in Bandar Seri Begawan in August 1988.

The Malaysian curator was Harold Reagan Eswar, also a visual artist based in the state of Sabah and a member of Cracko Art Group (CAG), whom I have met more recently during the planning stages of “Silingan Seni” (Artistic Neighbour) in Kota Kinabalu more recently in October 2015. “Silingan Seni” is an art project between Mindanaoan and Sabahan visual artist communities to be implemented in Zamboanga City in November 2017. This was realized through an artist reach-out project to personally meet CAG and Pangrok Sulap members in Sabah through the support of the International Affairs Office of the NCCA and the visual artists’ network of Sabah Art Gallery.

Re/imagining the SEA:

The Sky’s the Limit 2

“Under One Sky” attempted to re/connect the island region.

For the viewer, “Under One Sky” offers something familiar—the colours, the forms, the use of spaces, the imagery, and perhaps tastes—as one tries to absorb and comprehend the meaning of the artworks on display. Sometimes, it takes time to understand the meaning of each art piece, or the thread that weaves the stories of the region together.

The visual arts become a window that opens to a wider landscape of thought. We look into the minds of each artist as he or she makes sense of his or her local world. We should be willing and open participants to understand and experience the visuals encountered on display.

Is there something common and different? Is there something recurring in the imagery presented? We will notice the shared heritage in the EAGA region as well as the different directions these nations have taken toward their imagined destinies.

What are the visuals about? As we let our perceptions flow, we see representations on celebrations of history and the living heritage; the mundane and the everyday life; and communities trying to make sense of natural and man-made disasters. Other visuals challenged us to face mortality

and disgust; assertions of gender equality and self-determination of indigenous communities; personal beliefs and politics; and the culture of peace clashing head on with extremism to counteract this belief.

In this mid-centennial celebration of the ASEAN, this EAGA exhibition that for so long has been hoped had finally arrived. Perhaps, this thread of weaving stories through visuals should be pursued in the next incarnation of Budayaw for the next generation of Southeast Asian artists and viewers. Let us open our minds, our hearts, and our human spirit to the possibilities of art.

Celebrating History and the Living Heritage

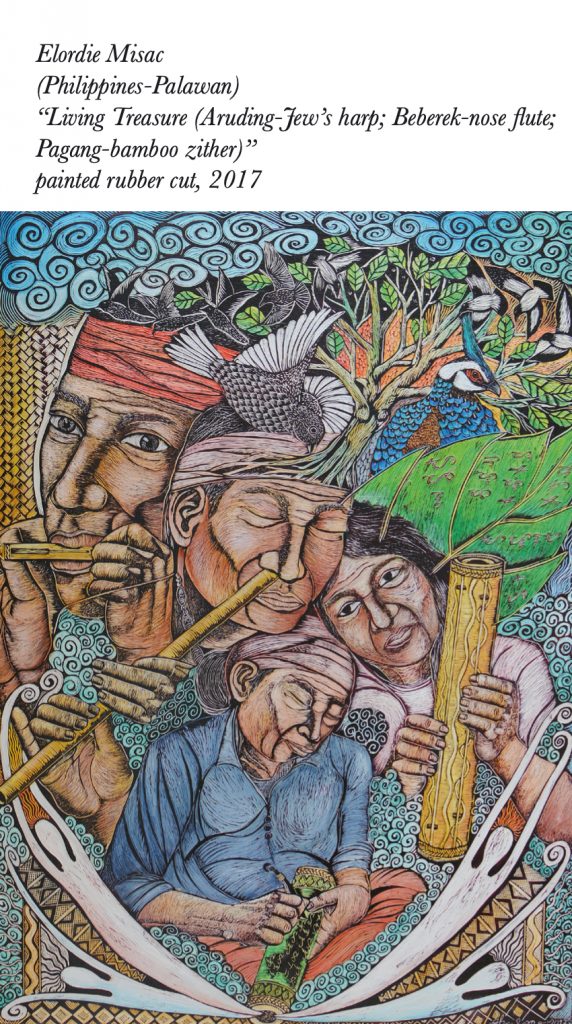

As one enters the exhibition space, the viewer sees the carving of Raymond Tangiday (Philippines, Davao) entitled Once Upon a Pre- Colonial Time (jackfruit wood, 2014) that harks back to the proto-Filipinos’ early beginnings encapsulated in the cosmos and notions of earthly, sea life, and the afterlife. Then we are led to hear and see the performative translation of Leonardo Rey Cariño’s (Philippines, General Santos City) Madal Blaan (enamel on canvas, 2017), his engagement with the Blaan communities in the South Cotabato through the drippings and the vibrancy of the colors on the large canvas. His work is bookended by Joel Geolamen’s (Philippines, Davao del Norte) Kabilin (Maguindanao) and Kabilin

(Tausug) (both acrylic on canvas, 2014),where the distant landscape and the textile weavings are juxtaposed as one entity, a metaphor for the land of the Bangsamoro peoples and their diverse cultures. Towards the left of Tangiday is Muhibbah (Goodwill) (mixed media painting on panel, 2017) by Pg Khamarul Zaman Pg Haji Tajuddin (Brunei Darussalam), whose decatych encompasses three exhibition panels reflecting the first encounter with another culture with cheerful acquiescence through the golden glow and the petal-like forms (of the hibiscus) that traverse across the painting.

In the obverse is the diptych Lantaw (Truth is Relative) (inter-media, 2015) of Rogelito D. Cayas, Jr (Philippines, Davao), where the pillars of Mindanao society (the lumad) are edified in angular and circular haloes and reinforced with the words home and domain. Across is Cariño’s Falmimak at Tenonggong(enamel on canvas, 2017), which reprises his homage to the Blaan culture, and the mandala-like rendition of Kulentangan (2016), Anoy Catague’s (Philippines, Davao) acrylic-on-canvas translation of the percussive harmony of the brass instruments common not only in the Philippines but across Southeast Asian neighbouring cultures.

The Mundane, the Everyday Life and the Voices of the Feminine

In the same breadth, the EAGA is not a utopian region, where eschewed progress is felt across the sectors of society and politics rears its ugly head in Edrick F. Aguirre’s (Philippines, General Santos) Basurahan (oil on canvas, 2013) as an exasperated expression sculptural piece of Michelle Hollanes Lua’s (Philippines, Cagayan de Oro) Maria Santisima (fiberglass, rice husk and light fixture, 2011). The title may also be the empowered vocal expression of women in a patriarchal world. Aguirre adds another work by redeeming the hopelessness as a testimony to the resurgence of human spirit in his Ahon (oil on canvas, 2017).

Though the sub-region is dominated by diverse traditional cultures, manufactured forms symbolized the notion of change, which is covered by traditional Subanen motifs. Tradition and change are always intertwined as depicted in the large relief work entitled Synergy 2 (mixed media, 2016) by Chester Mato (Philippines-, Zamboanga). This work resonates with Catague’s visually percussive piece entitled Spirits Within (Gimbao) (acrylic on canvas, 2016), where he depicted the strength of tradition over the changes in the early twenty-first century.

Along the same lines are the two works of Jericho Antonio Vamenta (Philippines, Cagayan de Oro) entitled Postura and Dumagat (both oil pastel on paper, 2014), where he presents in the former an opposing view of ourselves of being pretentious as dictated by our changing lifestyles, and in the latter of being true to oneself in one’s daily existence without a facade.

And to exemplify the notions of sensitive masculinity and empowered femininity, the portraits of a Tagbanwa couple from personal and imaginary encounters of Frances Mary Mendoza (Philippines, Palawan) entitled Natura Humana 1 and 2 (both mixed media on canvas, 2017) resonate with similar works entitled As-Samad (two works, mixed media paintings on glass and photograph, 2009) of Maziyah (Brunei Darrusalam). The latter’s symmetrical and geometric patterns depict a sense of order and countenance to the strength of the figurative portraits of the former.

This idea is further buttressed by the works The Prayer of Peace (2017), an acrylic –on-canvas piece of Gerald Goh (Malaysia, Sarawak) that signify the strength of quiet reflection of a woman in spiritual communion as depicted amidst organic forms. This work contrasts with Michelle Hollanes Lua’s second fiberglass piece The Last Suffer (2013), where a woman’s gaze is impaled and blinded by a relief of laced-like material.

Notions of War and Disorder

If the viewer opted to go towards the right of the exhibition upon entering, a set of works open them to the contradictions reflecting the Mindanao region. One is confronted by Al-Nezzar Ali’s (Philippines, General Santos City) installation of a headless camel and strewn masks entitled Remember Marawi: When the Unta-Unta Must Die! (In the Age

of Extremism) (2017) and the gazing Hasnah’s Pilgrimage (2013), the faceless sculptural hijab of Alynna B. Macla (Philippines, Davao del Norte). Both artistic pieces reflect different realities facing the Moro communities in Mindanao. Both can be personal, and the ramifications of divergent beliefs can affect the society for better and worse. Ali’s piece confronts us—a violent disposition towards extremism over the centuries-old culture that nurtured our ancestors, while the Macla’s work is a woman’s personal journey being a Muslim in a culture of peace. In addition, a layer of appreciation for non- Moro viewers gazing at Macla’s work might be a reflection—Who is my Muslim/Moro neighbour?

More works depict a recent tragic event in Mindanao—the Ramadan attack on Marawi City (in Lanao del Sur) by local and foreign adherents of extremism on 23 May 2018 as seen in the works of Ray Malicay’s (Philippines, Cotabato) Firebird and Teardrops for Marawi (both acrylic on canvas, 2017), and a satirical series on the intentions with some individuals in the military brass in the Mindanao as seen in the series of Rameer Tawasil (Philippines, Zamboanga) entitled General Merchandise (four works, graphite on paper, 2016). Malicay’s entangled thread-like lines reflect the turmoil of the land. One can only imagine, if sense of order is restored, they might look like the inaul textile from his province, while Tawasil reflects the vacillating trust and mistrust with government in dealing with the ongoing Moro rebellion in the South due to their unresolved marginalisation even after these communities became part of the Philippine Republic since the annexation of the archipelago by Spanish and American colonizers.

Finding Empathy in Tragedies

“Under One Sky” also tries to make sense of the recent natural and man-made disasters in the EAGA. For the former, Chris Pereira’s (Malaysia, Sabah) Ranau Post-Earthquake: Determination and Ranau Post-Earthquake: Education (both C-prints, 2015) picture community resilience in the face of a natural tragedy (that is, the 2015 Mount Kinabalu earthquake in Sabah) and on the fragility of our short life. For the latter, human folly is rendered destructive with the typing of words and texting, and in social media platforms as rendered in bomb-like form of Oscar Esteban Floirendo’s (Philippines, Cagayan de Oro) WMD (Words of Mass Destruction) (mixed media assemblage, 2016). Or in the mean streets of the everyday as painted still-life rendition of doors of urban poor dwellings by Michael Bacol (Philippines, Cagayan de Oro) in his Tokhang Passage 1 and 2 (both oil on canvas, 2016), and in the dripped rendering of a regenerating deathly body of a person in Melissa Abuga-a’s (Philippines, Misamis Oriental) Left of the Murder (acrylic on canvas, 2017). Bacol’s and Abuga-a’s works remind us that human life has been devalued further with the reign of impunity and the rising body count in drug war of the current administration. Furthermore, Faizal Hamdam (Brunei Darussalam) makes us reflect our existence differently. Stereotypically, human skulls are reminders of death and mortality. Equally important, he sees Who We Are (four pieces, acrylic on canvas, 2017) as an expanded notion that we can perpetually “smile” at each other devoid of our flesh.

Common Roots and Common Ideals

Tawasil’s sole representative of his series, entitled Bajau, Great Diver of the Sulu Deep (gouache, acrylic and oil on paper, 2017), acknowledges the Sama Bajau communities of Sulu, and reflects the migratory fluidity of people in the EAGA, making our cultures interrelated. After all, we are generally alike and intertwined in the use of some of our local words, the livelihoods that connect to the land and the sea, our overlapping genealogies, and shared sentiments. Besides those mentioned, we also have shared geography, flora and fauns, and the cosmos above us as seen in the works of Yusoph’s photographs, The Last Catch and Father and Son (both C-prints, 2017); in Umi Zaty Bazillah Zakaria’s (Brunei Darussalam) Galaxy (mixed media painting, 2016);in Emma Prima’s (Philippines, Zamboanga) Village by the Sea (oil on canvas, 2017); and in Abuga-a’s Nesting Peace (acrylic on canvas, 2017).

Finally, the themes of nurturing nature and the importance of giving respect to the original owners of the land and our sub-regional universe are highlighted in the following works: Goh’s Hornbill and Dragon 2 (acrylic on canvas, 2017); Cayas’s Lantaw (inter-media on panel, 2015); Osveanne Osman’s (Brunei Darussalam) Mystic (mixed media painting, 2017); Prima’s The Ruins (oil on canvas, 2017); Harold Reagan Eswar’s (Malaysia, Sabah) interestingly minimally rendered paintings, which are entitled Bila masa sudah sampai (When the time comes), Bila tanah sudah dijual (When land is sold), Bila kita sudah tiada (When us is no more) and Bila semua sudah tahu (When all knows) (four works, acrylic on canvas, 2017); and Raul Bendit’s (Philippines, Bukidnon) paintings entitled Katyapi ni Nanay and Tagapangubing (Player of Kubing) (both in soil, 2016). Bendit represents their Talaandig ancestral land, literally and metaphorically, on his canvasses by binding various soil pigments with glue and acrylic.

Sharing of Profound Artistic Meanings to the Community

The artistic efforts in “Under One Sky” would all come to naught without the foresight, planning and the implementation of a sound audience development program by the Budayaw 2017 secretariat, especially with the early linkages with the Department of Education and with private and public elementary, junior and senior high schools in and around General Santos City and South Cotabato. The outcome was favorable on-site experiences through the event managers, all of whom were the mentors and student members of the Mindanao State University’s (General Santos) Pinta Okir Visual Art Guild.

“Under One Sky” strengthens viewer engagement with art talks and interactive workshops at the Veranza Mall Atrium. In the three-day art talks, visual practitioners from the EAGA were represented by Michelle Hollanes Lua (Philippines), Lorna Fernandez (Philippines), Jericho Antonio Vamenta (Philippines), Rameer Tawasil (Philippines), Harold Reagan Eswar (Malaysia), Chris Pereira (Malaysia), Faizal Hamdam (Brunei Darussalam), Al-Nezzar Ali (Philippines), and Abraham Garcia, Jr. (Philippines). In addition, the presence of Joyce Toh, co-curatorial head of the Singapore Art Museum, as keynote speaker and as one of the Budayaw Colloquium resource persons underscored the contribution of EAGA visual artists to contemporary Southeast Asian art scene.

The Papercraft Architectural Puzzle Workshop, facilitated by Ryan Arengo of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, which saw the construction of iconic landmarks of the BIMP-EAGA such as the Grand Mosque of Cotabato (Philippines), the Atkinson Clock Tower in Kota Kinabalu (Malaysia), the Tongkonan Traditional Rice Barn in South Sulawesi (Indonesia), and the Jame’ Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque in Bandar Seri Begawan (Brunei Darussalam), added to the value of EAGA in the cultural milieu of students from General Santos City and South Cotabato.

And there was the Balay-Balay Architecture Puzzle activities featuring the Meranaw torogan, which was facilitated by architect Gloryrose Dy-Metilla and Marben Jan Picar. The talks on heritage architecture and design were led by architect Henna Dazo of Swito Designs. These activities emphasized the importance of nurturing our cultural heritage focusing on traditional dwellings in a globalized twenty-first century.

The Veranza Mall Atrium was also the venue of on-site performances featuring the Holy Trinity College Kulintayaw Cultural Performing Troupe during the “Under One Sky” opening; the Kulintangan Maguindanao during the whole exhibition with culinary delights brought by the Sugoda Buayan Royal Heritage community; and the impromptu on-stage performances of participating and visiting artists from Mindanao and Palawan.

To emphasize the value of artistic engagement in “Under One Sky,” a serendipitous and unplanned activity happened at the visual arts exhibition. It became an occasion when the Malaysian delegates (not the visual arts) performed the joget lambak (a form of community dancing) accompanied by music played on the gambus (guitar-like instrument). For all present at that moment, a profound realization descended among the artists and the public that in order for EAGA to thrive in the bigger ASEAN, we should have more of these non-verbal (and performative) engagements together more often than not.3

Endnotes

- Al-Nezzar Ali, event director, Budayaw 2017. The “Under One Sky” concept was prepared prior to the first official meeting in Davao in February 2017. It had undergone different iterations, and at times it lost and found its way, as the Budayaw 2017 preparations were underway.

- Abraham Garcia, Jr., Mindanao-based practicing artist, art educator and cultural worker. “Re/imagining the SEA: The Sky’s the Limit” is the curatorial note of the “Under One Sky” exhibit. For this pioneering undertaking in the EAGA, the exhibition featured 30 artists from the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei Darussalam.

- Joget lambak was performed on 23 September 2017 at the “Under One Sky” exhibition venue by the Malaysian delegates with the interaction of the students, the participating and visiting artists, and the viewing public. It was reprised the following day with a different set of viewers.

Bibliography

May, Vanessa. “Personal Life in Public Spaces.” In Sociology of Personal Life, edited by Vanessa May, 109-120. Croydon: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

__________. “Conclusion: Why a Sociology of Personal Life?” In Sociology of Personal Life, edited by Vanessa May, 168-172. Croydon: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Simmel, George. “The Field of Sociology.” In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited and translated by G. Wolff, 7-9. NY: Free Press, 1950.

Tilley, Charles. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford: Berg, 1994.